Tinto, Odiel and Piedras Basin (Spain)

Natural Environment

The Tinto, Odiel and Piedras basin is located in Andalucia, southwestern Spain and occupies the central-southern sector of Huelva province, between the Guadiana and Chanza rivers to the west and north and the mountain front of the Sierra de Aracena to the east, extending southwards to the Atlantic coastline in the Gulf of Cádiz.

The catchment system covers 4.762 km² of which 98% corresponds to the province of Huelva and 2% to the province of Seville (Junta de Andalucía, 2022).

Geomorphology

The Tinto, Odiel and Piedras catchments extend from the softly contoured northern uplands of the Sierra de Huelva to the flat Atlantic coastal plains (Olías et al., 2008). Only a small sector of the Sierra lies within the basin, forming the headwaters of the Odiel and Tinto rivers (Junta de Andalucía, 2022). Here, rounded ridges and narrow valleys host chestnut and pine forests at higher elevations, while lower and mid-slope positions show mosaics of Dehesa, abandoned eucalyptus stands and degraded shrubland shaped by grazing and recurrent fires (Domingo-Santos & Corral-Pazos de Provens, 2025). This abrupt transition from serrano relief to rolling piedmont sets up the basin’s characteristic north–south gradient (Olías et al., 2008). Southward, the landscape opens into the Andévalo, a broad hilly zone dominated by these dehesa landscapes, combining open woodland, shrubland and pasture (Olías et al., 2008). This unit forms the morphological bridge between the uplands and the more dissected central belt. Further downstream, the Cuenca Minera presents a more dissected relief structured by a dense drainage network (Olías et al., 2008) and shaped by a long history of mining activity in the Iberian Pyrite Belt (Cáceres et al., 2023). Toward the lower basin, the Condado forms gently undulating terraces and plains that gradually merge with the Costa, where sandy deposits, dunes and coastal marshes such as the Marismas del Odiel define the Atlantic fringe and the outlet of the basin. These coastal formations mark the final flattening of the basin and illustrate the progressive smoothing of relief toward the Atlantic (Olías et al., 2008).

Geology

The geological organisation of the Tinto, Odiel and Piedras basin mirrors the north–south arrangement of Huelva’s major terrain units (Olías et al., 2008). At the northern margin, a narrow fringe of the Ossa-Morena Zone enters the basin, composed of Precambrian to Palaeozoic schists, greywackes, black quartzites, slates and interbedded amphibolites and volcanic rocks, all strongly deformed and cut by major fracture and shear zones including the Aracena Metamorphic Belt (Olías et al., 2008). These ancient metamorphic and igneous rocks form the structural core of the northern uplands (Olías et al., 2008). South of this boundary, the succession shifts into the South Portuguese Zone, which dominates almost the entire basin (Olías et al., 2008) and represents one of the most distinctive geological provinces in Europe (Olías et al., 2008). Its Middle Devonian to Permian volcano-sedimentary formations host the Iberian Pyrite Belt, internationally recognised as the region with the greatest concentration of massive sulphide deposits in the world (Olías et al., 2008), a volcanic-hosted massive sulphide province formed by submarine hydrothermal activity (Nieto et al., 2013). The exposure of these sulphide-rich units underpins a mining history that stretches back around 5000 years, with major activity during the Roman period and a strong intensification during the last 150 years (Cáceres et al., 2023). Weathering of these sulphide-rich materials generates acid mine drainage that affects not only the Tinto and Odiel but also their tributaries and associated streams, producing highly acidic and metal-rich waters throughout the basin (Nieto et al., 2013). Further south, the Paleozoic basement is overlain by Neogene and Quaternary marls, sands and alluvial deposits of the Guadalquivir Basin (Olías et al., 2008). Toward the Atlantic margin, these Neogene–Quaternary units are in turn covered by unconsolidated coastal, estuarine and aeolian sediments that form dune systems, sandy littoral deposits and the estuarine complex of the Ría de Huelva (Olías et al., 2008). Along this transect, the exposed rocks also show a marked age gradient, with the oldest materials in the north and progressively younger formations toward the coast (Olías et al., 2008).

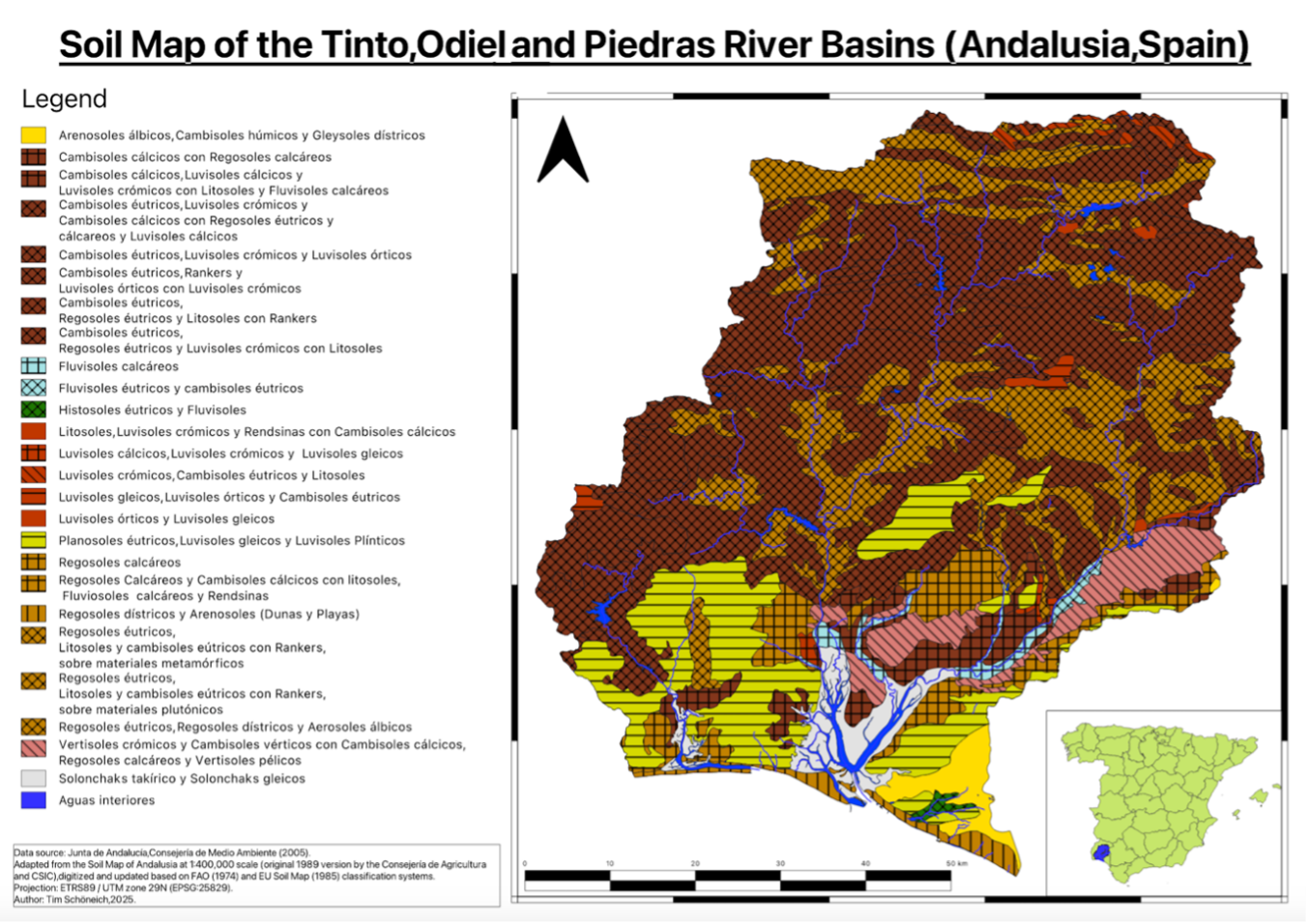

Soils

In the northern uplands on Paleozoic schists, quartzites and slates, shallow stony Cambisols are common (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025), with Leptosols and Regosols on convex and upper slopes (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025), profiles are thin and often poor in fine earth and organic matter (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025), and sheet erosion helps keep them shallow (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025). Across the Andévalo and the Cuenca Minera the substrates remain mainly siliceous so Cambisols and Leptosols are still prevalent (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025), while local basic intrusions can yield deeper clay-richer profiles with higher water holding capacity (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025). In mined zones, soils formed on residues are very acid, nutrient poor and structurally weak (Fernández Caliani & Barba Brioso, 2008), and natural regeneration is limited (Olías & Galván, 2008). In the Condado, clayey and marly Neogene and Quaternary deposits give rise to Vertisols that are very abundant between Niebla and La Palma (Olías & Galván, 2008), and Calcisols develop on marly or calcareous facies (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025). Toward the coast and the campiña belts, very deep sandy Arenosols are widespread (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025), and along the lower river courses Fluvisols occur on terraces and back swamps with stratified young profiles and local salinity near the estuaries (Domingo-Santos & Corral Pazos de Provens, 2025).

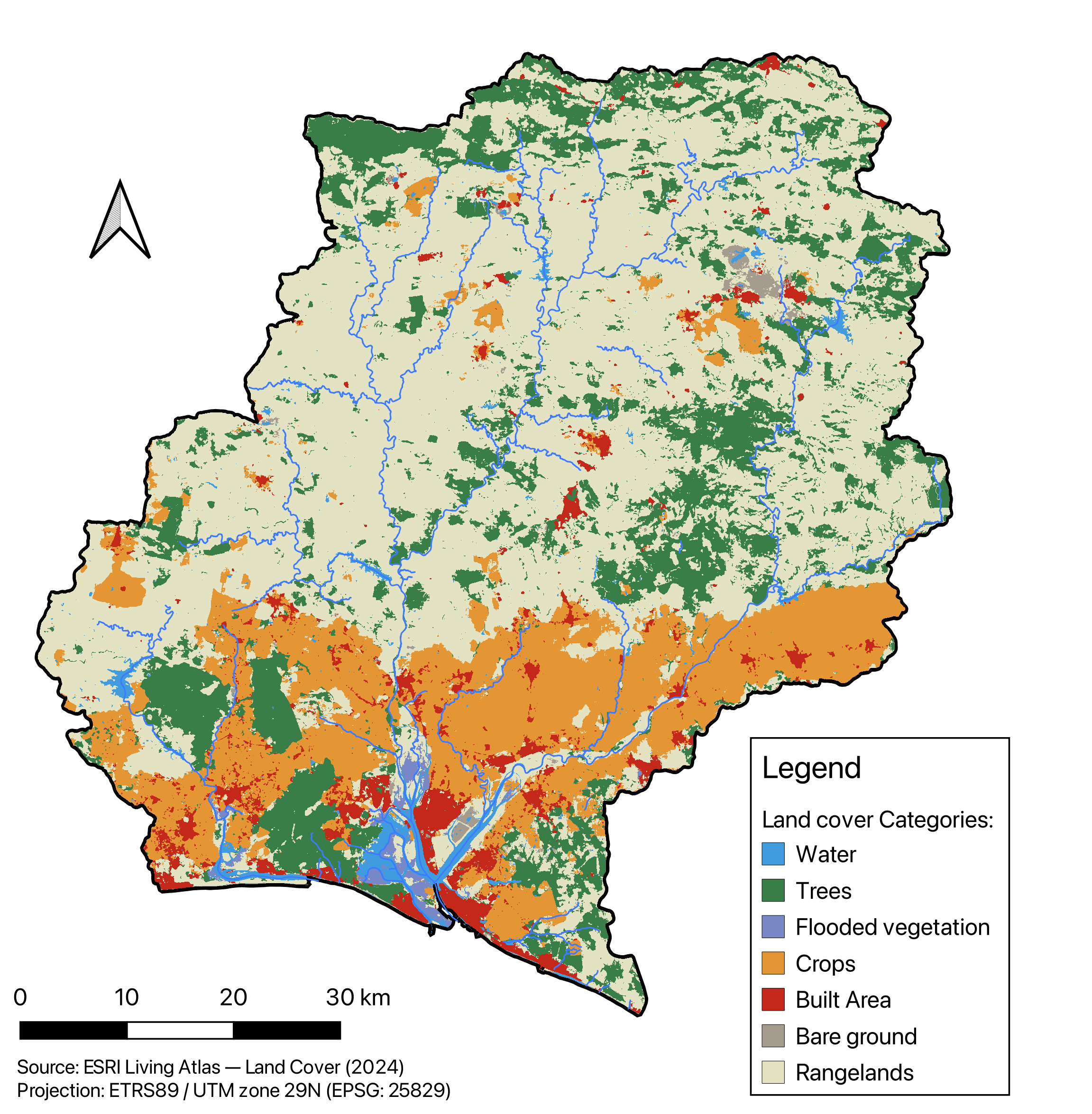

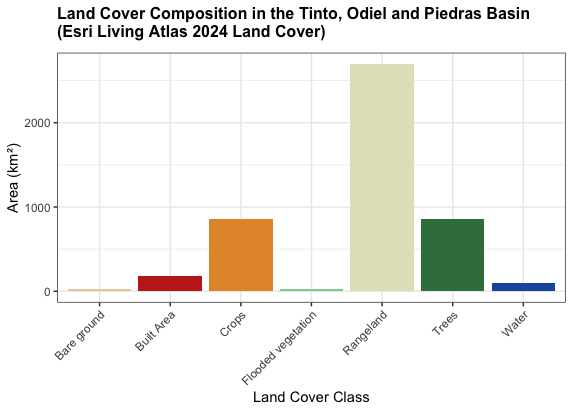

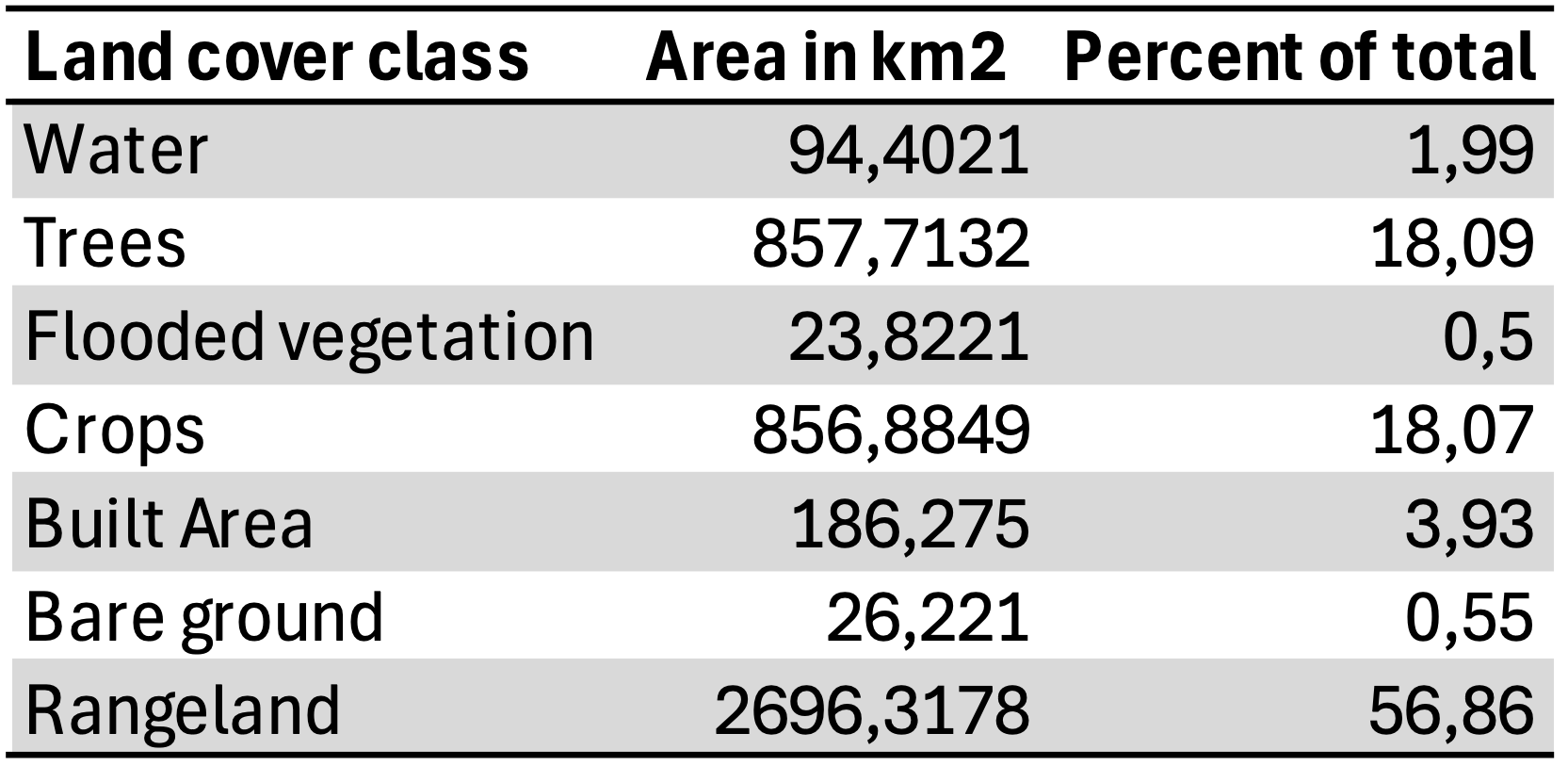

Landuse

References:

Cáceres, L. M., Ruiz, F., Bermejo, J., Fernández, L., González-Regalado, M. L., Rodríguez-Vidal, J., Abad, M., Izquierdo, T., Toscano, A., Gómez, P., & Romero, V. (2023). Sediments as sentinels of pollution episodes in the middle estuary of the Tinto River (SW Spain). Soil Systems, 7(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems7040095

Domingo-Santos, J. M., & Corral Pazos de Provens, E. (2025). Suelos forestales de la provincia de Huelva: Propiedades, evolución y distribución territorial. Huelva: Editorial Universidad de Huelva.

Fernández Caliani, J. C., & Barba Brioso, C. (2008). Suelos contaminados por actividades mineras. In Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales (Ed.), Geología de Huelva: Lugares de interés geológico (pp. 87–88). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva.

Junta de Andalucía. (2022). Plan Hidrológico 2022–2027. Demarcación Hidrográfica del Tinto, Odiel y Piedras: Memoria. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía.

Nieto, J. M., Sarmiento, A. M., Cánovas, C. R., Olías, M., & Ayora, C. (2013). Acid mine drainage in the Iberian Pyrite Belt: 1. Hydrochemical characteristics and pollutant load of the Tinto and Odiel rivers. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 20, 7509–7519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-1634-9

Olías, M., & Galván, L. (2008). Los suelos. In Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales (Ed.), Geología de Huelva: Lugares de interés geológico (pp. 50–52). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva.

Joffre, R., Rambal, S., & Ratte, J.-P. (1999). The dehesa system of southern Spain and Portugal as a natural ecosystem mimic. Agroforestry Systems, 45(1–3), 57–79.